- Home

- Janice Warman

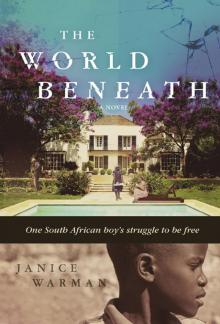

The World Beneath

The World Beneath Read online

Part One:1976

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Part Two:1976–78

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Part Three: 1978

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Glossary

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

If he stretched his fingers out in the dark, he could feel a damp wall. His head throbbed. How long had he been here? He lay quietly. There was an earth floor beneath him. His hands — he brushed the earth off them, then ran them over his face. It was sticky, and when he touched his nose, he cried out. One eye was swollen shut. On the back of his head, he found the source of his pain: a lump so big that it filled his hand.

It was quiet — a hollow kind of quiet that made him think he was alone in this place, wherever it was. He held his breath and listened. No birds sang. Yet this place must be in the veld. Perhaps it was a village. His stomach clenched in fear as he looked for a chink of light. Even at night a little light should leak in around a door; even in the country there was moonlight, starlight; even in the country there was movement, little rustles as things ran through the grass. Yet there was nothing. Perhaps he was dead. No, if he were dead, he would not feel pain. Or thirst. He was so thirsty. He felt around for a cup. Had someone left him some water?

He lay still again, with his dizzy head turned to one side, and resolved to think and to breathe slowly, to calm himself, to gather his strength so he could get out of here. He ran his hands over his body. He was dressed. He wriggled his toes. He had no shoes on, but his feet felt OK. Sometimes they went for your feet. Then, just as he thought, I am going to roll over onto my hands and knees, crawl to the wall, and try to stand —

The boy woke up. He was lying behind the comforting bulk of his mother. His heart was thudding fast. He shot out of bed and crouched against the far wall, arms over his head. “No!” he whispered before he could stop himself.

Then it came to him. The dream was about Sipho. In the dream, he was Sipho. His big brother, his strong, tall brother, who could swing him around and carry him high on his shoulders, Sipho with the deep laugh and wide, handsome face.

Before he’d thought what he was doing, he had shaken his mother awake. “Mama! Mama!” he sobbed. “Sipho! Sipho — he is hurt! I dreamed — I dreamed —”

His mother woke instantly. “No,” she said gently. “No, he is working in Jo’burg and he sends us money. You know that. You mustn’t worry.” Slowly, he stopped crying and fell asleep again while she lay looking into the darkness, her arms around him, tears streaming down her face.

Presently, she saw threads of light between the door and its frame and slipped out of bed, disentangling her arms from the small body. Sipho used to sleep like that too, before he became a man. Before he went away to Jo’burg to earn a living. Before he sent money back to her in Cape Town and to her parents in the Ciskei, for her younger children. Before —

By this time she had crossed the yard and gone up the red stone steps to the back door. She slipped her key into the lock and raised a hand to her doek, tucking the scarf in neatly at the back. It was almost time to take up the tea.

Beauty! Beauty! Where are you?” Mrs. Malherbe came rushing down the corridor and barged through the green baize door. “We need to sort out the menus before I can . . .”

Quickly, Joshua jumped into his hiding place by the kitchen. It was under the back stairs, which led out of the servants’ hall, up to the first floor. It was a perfect space for him, and he sat here when he could, listening to the sounds of the house.

It was like a little room, a cupboard, really, into which the vacuum cleaner and the polisher were crammed. There wasn’t much space left over, but there was enough for a boy with no shoes to crawl into the musty wooden dark. Joshua had pulled an old blanket in there once, one he had taken from Betsy’s basket. She was a basset hound, who sometimes let him crawl in with her and give her a cuddle. There was a big fuss over the missing blanket. His mother had to swear that she hadn’t taken it home or sold it.

“Sold it?” she fumed, as they sat in the damp paraffin smell of her room. “Why would I want to sell that old thing?” That was the trouble. They always thought you were stealing from them. Joshua didn’t tell his mother he had the blanket, but she caught him anyway. She was getting the Hoover out of the cupboard when she found it.

“Hayi,” she said. “You have shamed me in front of the Madam. We must give it back.” But he begged and pleaded, and in the end she left it where it was. At least that way, he supposed, she could say it had just somehow gotten into the cupboard; she didn’t know how.

And it meant he was out of the way. In fact, he wasn’t meant to be in the house at all. He should have been in the country with his grandparents. But Mrs. Malherbe was turning a blind eye, which was what these people did when they wanted to help you. Other times, they said, “How can I believe you?” or “You can’t fool me — I’m not stupid.”

They were, though. Most of them. How many of them could speak three or four languages? How many of them could run a house that size, cleaning it through every day, making the beds, doing the washing and the cooking, and still look after a set of fractious white children?

It seemed that most of them couldn’t do anything at all. It took Mrs. Malherbe most of the morning to get up. Then she had coffee and buttered Provita by the pool and listened to Woman’s Hour. After swimming ten lengths, she showered. Then she went out in her car. It was a dark green MG, and it made a throaty roar as it went up the road. Joshua loved that car. He washed it and polished it for her, twisting the cloth into little corners to get the last of the polish out of the little runnels under the windows and buffing the chrome bumpers until they shone.

When he knew she was having a lie-down (something she did almost every afternoon), he sat in the tan leather driver’s seat, running his hands over the cool steering wheel, gazing ahead down the driveway between the rows of smoke-blue hydrangeas, seeing the open road.

He was glad the Malherbes didn’t have children, only a grown-up son who belonged to the Madam. He could hear the Websters across the road in the afternoons, and he shuddered. There were six of them: they screamed and fought and dive-bombed one another in the pool. Their mother shouted at them. But it was quiet by the time their father came home, and as dusk fell over the lawns, under the great gray back of the mountain, there was nothing to hear but the little hiss of sprinklers spitting and turning, spitting and turning.

Mr. Malherbe liked supper on the table at seven. There was, in consequence, a flurry of activity around six, when Mrs. Malherbe emerged pink-eyed from her bedroom and, clutching a gin and tonic, supervised the making of the supper and the setting of the table.

As far as Joshua could see, she did nothing but get in the way. She fussed and she tutted; she moved things; she tasted, screwing up her f

ace; and as seven approached, and the second gin and tonic was poured, she retreated, combed her hair, put on a slash of red lipstick, and sat in the front lounge with the newspaper on her lap. At the sound of her husband’s Mercedes, she held the paper up and looked earnestly at it. And there she would be when he came in.

The child was supposed to go to bed after supper in his mother’s room, which was across the yellow dirt yard from the main house, between the garage, the workshop, and the outside bathroom. He would curl up in the sagging bed by the damp and peeling wall, head under the covers to keep out the light and the ceaseless sound of his mother’s knitting machine. Often he would creep back to the big house across the yard, up the slippery red-polished steps of the back stoep, and curl up under the stairs, where it was warmer, and where now and then Betsy would crawl in with him.

He would hear them in the next room, having supper. Usually there was just a quiet rumble of talk; sometimes a shrill burst of laughter from Mrs. Malherbe. Sometimes he fell asleep, snug in his hairy cocoon, and woke to find Betsy snoring comfortably beside him. He would open the back door quietly, clicking the Yale lock shut behind him, and tiptoe out, the beaten yellow dust cold under his feet, and slip into bed behind his mother, staring into the darkness until sleep took him.

Often he would dream strange dreams that he knew were about Sipho: one night, a ring of mountains above his head, and he as small as an ant on the grass; in another, he was back in his grandparents’ house in the Ciskei, hiding under the table with his little sister, Phumla, and giggling among the grown-ups’ legs. Or he was all squashed up to one side in the back of a car; there was a cloth around his face, and he could only just breathe. His arms were tied behind him. He wriggled over onto his back and felt the fresh cold air come through the window onto his hot forehead, and in the inky dark he saw stars, millions of stars. He was afraid. These were the dreams he hated the most, and they made him put off going to bed, even though his mother said Sipho was fine.

It was after supper one night, when he was in his hidey-hole under the stairs, that things changed. The tempo of the conversation quickened, and Mr. Malherbe’s voice deepened. Mrs. Malherbe’s voice ran quickly up the scale. He listened, holding his breath. She wasn’t laughing. She was crying.

Then Mr. Malherbe roared, Mrs. Malherbe screamed, and something smashed. The front door slammed, and Joshua heard the iron gates crash open and the Mercedes’s heavy tires squeal as it turned onto the road.

Beauty picked up the broken bottle and dabbed at the wine stain on the wallpaper, her broad forehead a crosshatch of wrinkles. Mrs. Malherbe was a hard taskmistress; every day she would run her finger along the mantelpiece or a windowsill. “What’s this, Beauty? What’s this?” she would hiss. “I pay you to keep the house clean.”

But she didn’t do it today. She rang the bell for lemon tea and then emerged, hair in a turban, gown carelessly tied. She swam for an hour, up and down, with her head raised, paddling like an ungainly duck, and when Beauty asked her what to make for supper, she said, “Oh, Beauty, I don’t know, you choose, I don’t care, really —” She twisted the gown close around her and went dripping up the stairs. There was a faint yellow bruise at the base of her throat.

“Will the Master . . .?” Beauty called after her, and trailed off. She turned and went silently, heavily, through the green baize door and into the kitchen.

The Master wouldn’t; seven o’clock came and went, and at eight a yawning Beauty served the dried-out lamb chops, the wilting salad, wiped down the sink and the stovetop, and went.

The following evening, Mr. Malherbe’s car turned in quietly through the gates and Mrs. Malherbe sat, mouth tight, looking carefully at the headlines and swirling her drink in the glass so that the ice cubes clinked.

Joshua quietly helped his mother in the kitchen, but he didn’t go through with the plates. They both knew that Mr. Malherbe did not like him to be there, and all three of them ensured Joshua was not seen in the evenings.

Afterward, they both hurried across the backyard to the room. Beauty set her knitting machine going.

Finally he had to ask, “Mama, Mama, why am I here with you still?”

Beauty stopped the machine. She came and sat on the bed by him. She sighed. “Joshua, you were so sick.” She took his hand and said, “We thought you were going to die.” Tears brimmed at the edges of her eyes. “That’s why I brought you to the city. I couldn’t bear to leave you behind. What if . . .?”

Joshua squeezed her hand. He remembered being ill, coughing and coughing, the fevers. He couldn’t breathe; a few times he had coughed up browny-red stuff that he later realized was blood. He remembered waking in the night. His mother was always there, sitting by his bed; the gas lamp would be hissing, and she would be stitching.

He had been frightened. There would be a moment each time he woke when he would feel that cramp of terror in his stomach; then he would see she was there, and he would feel a little calmer.

There was one visit to the doctor, a thin, pale man behind a desk, who had shaken his head over the red-stained cloth they had shown him. Then Joshua had to sit up on the high bed on a crackling white paper sheet and the man said, “I’m sorry, Joshua, this is going to be cold. It’s a stethoscope. I need to put it on your chest so I can listen to your breathing.” It tickled a bit and he giggled, then had a fit of coughing that ended with more blood in the bowl.

They went into another room and he had to stand very still with a cold, flat plate against his chest, and the nurse left the room (but his mother didn’t). Then there was a buzzing noise, and the nurse came back and slid out the big metal plate and put another one in. She told him to turn around and to stand very still again. Afterward, the doctor put the pictures up on a lighted panel; the light shone through the dark patches on the film.

“He’ll need tablets.” He wrote something on a piece of paper and handed it to Beauty. “It’s very important that he has them three times a day with food.” He turned to Joshua. “And you must finish all of them. Do you understand? We are lucky these days. Tuberculosis is curable. But you must take the tablets for a year.”

He was still weak and feverish, and the tablets gave him the runs, but after a little while he began to feel better. They put a chair for him outside the hut, and there he sat in the sunshine, with his head back and his eyes closed.

At night Joshua lay in the dark of the back room on his own, because his mother did not want his sister and brother to catch his disease. It was carried on the air, she said; he was not to touch them and not to cough if he was near them.

But then it was time for his mother to go back to the city. She had had a letter from Mrs. Malherbe: “Beauty, I have been very patient. But now I need you to come back. If you are not back by next week, I will have to look for another maid.” Then the arguments began.

His grandmother said, “Leave the boy with us.”

His mother said, “No. No, I cannot . . . No, he is coming with me.”

There was the big boom of his grandfather’s voice, and his mother began to cry.

“Your Madam will sack you!” shouted his grandfather, and then there was the softer sound of his grandmother’s voice, and his mother’s, high and keening. “Then what will we all do?” he roared.

When the day came, it turned out that Joshua was to go with her to the city. It was the Easter holidays, and he was to be sent back to his grandparents when school started again.

Joshua didn’t want to leave his sister, Phumla, and Xola, his younger brother. Phumla was small and thin, with little tight braids and big anxious eyes; she was his favorite. Xola was her twin, but he was sturdier and stronger; Joshua didn’t worry about him so much. When his mother was away, he looked after them. He had to get them ready for school and make sure they ate their breakfast.

They climbed up into the truck. Joshua didn’t know who was crying more, he or the twins. They clung to each other, sobbing. He leaned out the window. His grandmother stood behind

them with her hands on their small shoulders. His grandfather stood to one side, looking away, still angry.

But he had to be strong. He was their big brother. “Bye-bye!” he called down to them, waving. They looked so small. “Be good! I’ll see you soon!”

He leaned over and waved again. “I’ll bring you back a present!” he called.

Then they were off, bumping up the dusty track; he looked back and watched them getting smaller and smaller, waving. His grandfather, too, finally raised a hand, just before they turned the corner, and he couldn’t see them anymore.

“So why am I still here?” Joshua asked his mother again. “The holidays are over.”

Beauty hesitated. “I think it is better to keep you with me. It is safer.”

“Why?”

“Because — because . . . I do not want to send you back on your own. It is not safe to send a boy a long way like that all alone.”

“But why?”

She hesitated again. “Because Y’s a crooked letter and you can’t make it straight,” she said finally, and a smile transformed her round, anxious face. “Go to sleep now.”

Soon she was back at the knitting machine, and Joshua lay waiting to fall asleep to its comforting clatter, the smell of the damp plaster sharp in his nostrils.

He thought of his grandmother. When he came out with his blanket around him to sit in the sun at the front of their house, she would always open her arms to him and enfold him in a big strong hug.

“But, Grandmother,” he would say, “you are not supposed to hug me. I will make you sick!”

And she would just laugh and hug him again and kiss the top of his head. “Nonsense,” she would say. “I am so old I cannot get sick any longer. There is no sickness that I am afraid of now.”

She was a big woman, broad and strong. His mother had her high cheekbones and wide mouth. She was not afraid of anything, least of all his grandfather, though his grandfather was tremendously tall and thin and leaned forward wherever he walked, as if he wanted to get where he was going as fast as he could. He had a terribly loud voice and a quick temper, and if Joshua hadn’t grown up with them both and seen that his mother and his grandmother were not afraid of him, he would have found him terrifying.

The World Beneath

The World Beneath